Editor’s note: This article discusses suicide. If you or someone you know is struggling or in crisis, help is available. Call or text 988 or chat at 988lifeline.org.

Eight years since Rashaan Salaam died by suicide in Colorado, his girlfriend still feels the pain of his loss.

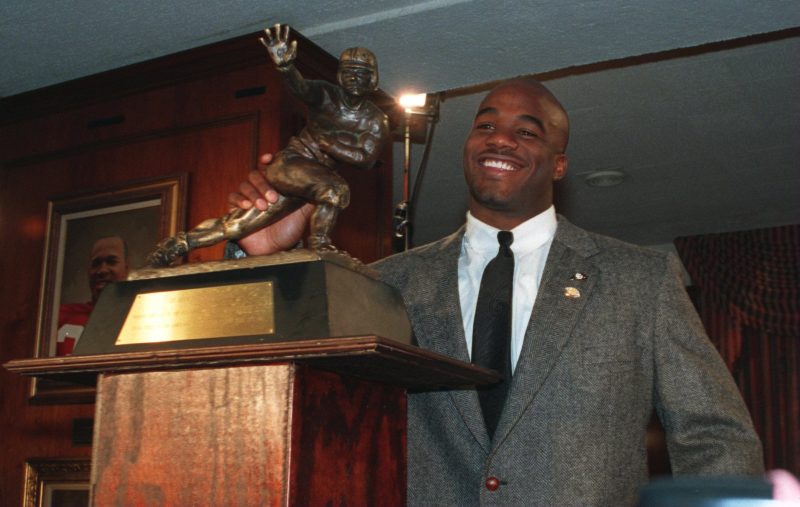

“Not one day goes by” that she doesn’t, said Salaam’s girlfriend, Shelley Martin. But she hopes the 30th anniversary of his Heisman Trophy win will renew interest in his memory, especially now that two-way star Travis Hunter is on the verge of winning Colorado’s first Heisman since Salaam won it as a junior running back at Colorado on Dec. 10, 1994.

“He’s just a beautiful soul,” Martin said of Salaam this week in an interview with USA TODAY Sports. “It needs to be told… about mental health and concussions. That is real. I saw it.”

This is normally a time of reflection for Salaam’s family and friends. He died on Dec. 5, 2016 at age 42. The Heisman Trophy ceremony usually comes shortly after that every year. Only this time it’s a little more personal. If Hunter wins it Saturday, they hope it raises even more awareness about Colorado’s first Heisman winner, thereby bringing more attention to suicide prevention and who Salaam was as a person.

In many ways, he was like Hunter – the gifted football player and humble homebody with the bright smile who often deflected praise toward his teammates.

“You can think you’re having a bad day and then just think back about Rashaan and the smile he always had,” his former Colorado teammate Derek West said this week. “It’s always uplighting. It kind of pulls you out of any funk you may be in. I just smiled thinking about it.”

Two Heisman Trophies at Colorado, 30 years apart?

Each year, two actual Heisman Trophies are given out – one to the college football player who wins it and one to that player’s school. Colorado still keeps its 1994 Heisman Trophy on display in a hallway that Travis Hunter has walked down many times 30 years later.

On Saturday, Hunter is the favorite to win another one for Colorado, according to BetMGM.

In Salaam’s case, he won the award decisively, rushing for 2,055 yards and 24 touchdowns in a magical 11-1 season when the Buffaloes finished as the No. 3 team in the nation. Yet Salaam didn’t like being singled out for it and instead credited his teammates on the offensive line for helping him gain all those yards. Ten of the 11 starters on that CU offense eventually were drafted into the NFL, including Salaam, all five linemen, quarterback Kordell Stewart and receiver Michael Westbrook.

“He was just the ultimate team guy, and I think we can all learn from that,” said West, who was one of Salaam’s blockers on that offensive line. West also helped carry Salaam’s body to his grave in Boulder after his shocking death.

“If Travis is fortunate enough to win the Heisman, and this brings any attention to Rashaan, the man that he was, and raise any awareness around suicide prevention, then that’s a win all the way around,” West said.

‘He never wanted to be out front’

Stewart, Salaam’s quarterback at CU, stressed the importance of remembering how he lived and who he was, not his death.

“He has (created) more memories of great things and the life that he lived to allow that one moment to deter us from remembering him for who and what he was to us and to his family and friends,” Stewart told USA TODAY Sports this week. “He was a great dude. Loved him to death.”

Stewart said Salaam was like a “little brother” to him who inspired his teammates in a “very quiet way.”

By that he said he means this:

“He never wanted to be out front,” Stewart said. “He just wanted to be a part of it.”

Salaam gave his trophy to his mom, then sold it

The Heisman might be the most famous individual award in American sports, given to the best college football player in the country. Salaam looked at it differently, however.

Not liking all the individual attention, he described the Heisman as a burden of sorts before he even won it – 45 pounds of heavy expectations that he didn’t always want. After winning it, he even gave it to his mother to keep at her home in San Diego for many years. He also gave his other trophies to relatives, including the Walter Camp and Doak Walker awards he won in 1994 as the nation’s top player and running back.

“He gave his trophies away, and he gave me the Heisman,” his mother Khalada told USA TODAY Sports this week.

But Salaam later asked her to have his Heisman sent back to him in Colorado near the end of his life. So she did. Shortly after his death, family and friends then said his trophy had been “lost” until it resurfaced at an auction in January 2018, when it was sold for nearly $400,000.

‘Please reach out to somebody’

The tragic death of Salaam isn’t his final chapter, however − not if his memory is kept alive and others can learn from it, as some of his friends and family said.

Salaam had sold his Heisman Trophy before his death, said David Kohler, president of SCP Auctions in California. It later was consigned out for auction after he died, with some of the proceeds set to be donated to research on chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), the brain disease linked to head trauma in football.

Salaam’s brother, Jabali Alaji, told USA TODAY Sports in 2016 that Salaam had “all the symptoms” of CTE, including depression. Whatever the cause, and despite that outward smile, his inner turmoil reached a breaking point in early December 2016, shortly before the annual Heisman Trophy ceremony that year on Dec. 10. He didn’t plan to attend that ceremony in New York.

“If someone is seeking to harm themselves or having that suicidal ideation, I just beg them to please reach out to somebody,” Martin said. “Because it leaves us as survivors of suicide. It’s horrible. If somebody has cancer or they’re hospitalized in an accident, that’s different. But when it’s self-infliction, it hurts even more. And it hurts every day. It’s like a pain that will never go away.’

A teammate of Salaam’s from the 1993 Colorado team, wide receiver Charles E. Johnson, also died by suicide in North Carolina in 2022 at age 50.

To better support young people navigating their own mental health challenges, Salaam’s mother has helped start The Rashaan Salaam Foundation. She hadn’t been following all of Hunter’s accomplishments this year at Colorado but hoped the attention trickled down to the foundation as people learned about the first Heisman Trophy winner at CU 30 years ago.

“It’s young, but it has the possibility of doing some really positive things in Rashaan’s name and that’s really important to us,” she said.

The aftermath

Thirty years after Salaam took his Heisman home from New York, the current whereabouts of that trophy aren’t publicly known. The person who bought it at the auction in 2018 was a sports memorabilia collector who didn’t want to be identified publicly, the auction company said.

In a strange coincidence, Salaam’s father, Sultan Salaam, 78, died last year on the same date as his son seven years earlier: Dec. 5. He previously was known by the name Teddy Washington and played at San Diego State under coach Don Coryell after a brief tenure as a freshman player at Colorado in 1963.

“It’s amazing,” Salaam’s mother said of that coincidence. “All of this stuff is amazing. If I allow myself, it’s just like it happened yesterday. But I won’t allow myself. I’m trying to do something positive with all of this, because it’s a lot to deal with. It really is.”

After his son’s death in 2016, Salaam’s father told USA TODAY Sports the Heisman was only a football award and didn’t define his son’s life.

He said then he hoped his son would be remembered as a “a team player.”

“That means together each achieves more,” he said. “Not by yourself.”

‘A celebration for us all’

Hunter has echoed that sentiment 30 years later. He couldn’t be reached for comment about Salaam. But in an email interview earlier this year with USA TODAY Sports, Hunter said the Heisman is “more than an individual award.”

“It’s a collective achievement and a celebration for us all,” he said in the email.

Likewise, Martin is rooting for him to become only the second Heisman winner in school history.

“Of course, we know those are some big shoes to fill, and (Hunter) went above and beyond,” said Martin, a Colorado graduate. “I’m just so happy to support our alumni. I’m grateful. To play offense and defense? Who can do that? It’s super awesome.”

West, the former teammate, has met Hunter and called him “a team guy,” much like Salaam.

He’s “down to earth, kind of always has a smile on his face as well,” West said. “I couldn’t think of a better representative for the university to win the second Heisman than Travis. He’s very similar to Rashaan in those characteristics.”

If Hunter wins the Heisman Saturday, it’ll be a “celebration for us all” at Colorado, as Hunter said – just like Salaam wanted it to be 30 years ago when he won the same trophy.

“Just like we all say, `We like to give the love to each other,’” Kordell Stewart said. “It’s never about one person.”

Follow reporter Brent Schrotenboer @Schrotenboer. Email: bschrotenb@usatoday.com